I'm tired and may be coming down with a cold, so that meant I felt perfectly well-occupied editing the blog's links. All done now, yay!

Slippery numbers

I haven't slept, and I went on a mondo hike today that I was in no way prepared for (which was actually really nice after being chained to my desk to push out Trust for so long), and I'm exhausted and should probably just turn the computer off and go to bed.

But, although I'm sure I am far from the first, I want to talk about two things I saw in Passive Voice the other day. (No, not today. I'm a little behind, OK?)

Thing #1: Barnes & Noble had crappy financial results, and is still losing oodles of money.

The interesting bit with the numbers: They're still maintaining that magical 27% market share in e-books! Let's tout that number some more! 27%! 27%! Rah! Rah! Rah!

But, hey, they're still losing oodles of money. Hmmm....

Yeah, that number's not worth much. Their financial results reflect my earlier point that e-books and e-book readers are not, in fact, the same thing. B&N has decided that those two businesses together constitute The Nook Business (which at least answers a lingering question on that front), but expect them to try to highlight whichever business is doing better and to ignore whichever business is doing worse. (In other words, expect press releases that go, "Business is great! We lost a billion dollars!" There are a lot of those.)

The other thing about that number is that, in the best-case scenario (you know, the scenario where they're not just making the number up out of whole cloth), it applies only to e-books produced by traditional publishers. B&N has not done a good job promoting self-published writers, but however this is hurting them, it's not going to be reflected in that magical, unchanging 27% figure. It going to be reflected in their financial results, though. (I will note that I find it...curious...that that market-share number never seems to change. They very quickly took this big hunk of the market, and just as quickly, their market share completely stagnated. That is...odd.)

Thing #2: Another claim that it costs almost as much to make an e-book as to make a paper book--80% as much.

This ones a little weird, because it's someone reporting (favorably, which is hysterical--he knows it doesn't add up, but he loves it and even calls it "smart") on another story that I can't read because I don't subscribe to the New Yorker. Obviously I think the overall claim is worthy of great scatology, but the main thing that struck my eye was this quote of a quote:

E-books are cheaper to produce, by about twenty per cent per book, because they do away with the cost of paper, printing, shipping, and warehousing. They also eliminate returns of unsold books—a significant expense, since thirty to fifty per cent of books are returned. But they create additional costs: maintaining computer servers, monitoring piracy, digitizing old books. And publishers have to pay authors and editors, as well as rent and administrative overhead, not to mention the costs of printing, distributing, and warehousing bound books, which continue to account for the large majority of their sales.

This doesn't make any sense. For starters, the author is including "the costs of printing, distributing, and warehousing bound books" in the cost of making e-books, which is like saying that your Kia cost almost as much as your Ferrari because you have to include the cost of buying a Ferrari in the cost of buying a Kia. He also includes the cost of maintaining computer servers, despite the fact that you totally don't have to.

But what I found really interesting is the line, "E-books are cheaper to produce, by about twenty per cent per book, because they do away with the cost of paper, printing, shipping, and warehousing."

Do you know what's not necessarily counted in the cost of producing a book? The cost of paper, printing, shipping, and warehousing! Depending on who is talking, production can mean what you do to get a book ready to be published: Line editing, copy editing, book design, layout, proofreading, cover art.

I could see e-books being 20% cheaper to produce if you don't count the cost of printing. I could see it if you count only the costs incurred to get a book ready to be printed or uploaded.

What do I think happened here? I think the reporter made some assumptions about what was meant by production, and the PR people just kept their mouths shut about what they actually meant.

I think I'll stick with the Wall Street Journal for my business news. The New Yorker guy clearly does not know squat about venture capital, either--it really cracked me up that he and I made the exact same analogy but meant such different things by it. (Another thing that really cracked me up was Mira's reponse to the article.)

Why I wish I wrote short fiction

Dean Wesley Smith has a great article on selling short fiction and all the different markets you can approach, including traditional and indie. He makes a good point, which is that the marketing value of getting a story published in a magazine makes it worth sending stuff there, even if the chances of making a sale are very low. I also think he has a point that you're probably better off bundling two stories and selling them for $2.99 than publishing them separately for 99 cents--it's making $2 one way versus making 70 cents the other, and that's going to add up. (Yes, you might lose impulse sales, but I think with the math being what it is, it's worth trying....)

Why the large-print edition was such a bear this time

You may have noticed that the large-print edition of Trust caused me no end of problems, which you might think puts the lie to my assertion that large-print layouts are easier to do than regular layouts.

The reason is was so difficult was simple: I didn't check the length, so I went long, and I had to narrow the margins to make the book the right length.

This was extremely tricky because with a large-print edition you do not indent paragraphs. Instead, you use block paragraphs. So there only thing indicating that two paragraphs are separate from each other is a line of white space caused by an extra hard return.

If you lay a book out in Word, like I do, guess how you force lines onto the next page? With an extra hard return! What about if the last line of a paragraph is the last line on a page? Well, then the next page starts with a white line, which is no good. So you remove that line by removing the extra hard return.

If the paragraphs are indented, it's really easy to recognize the difference between a paragraph break and anything you just moved around to make your layout work--the stuff you moved around isn't indented. You can see that simply by glancing over the layout.

With a large-print edition, the only way to tell those things apart is to actually read the text of the book again--carefully. In some cases I actually had to go to the regular edition to determine if I just sort of changed subjects within the paragraph or if I had lost a hard return.

Option B would have been to start the layout from scratch, but I don't think that would have saved me any time. Next time, I'll go with Option C, which is to be sure to estimate the page length first!

Trust got reviewed!

Trust got a really nice review in Futures Past and Present--yay! It's oddly nerve-wracking to speculate that someone who liked the first book might not like the second.

Argh, but look how much better he describes Trust than I do. He says:

When the book opens, the Cyclopes still on the station are starving. No one on their home planet has sent any food. That's because no one is running the government. They're all too afraid of offending the Magic Man after he killed most of the previous government, so no one wants to step up and take responsibility for anything. When Trang tries to find a solution to the problem, the Magic Man appoints him as interim head of the government. Which is a rather awkward position for a diplomat from Earth to find himself in.

Oh, did I mention that advancement in the Cyclopes government is by assassination?

That's so much better than what I have. I was just thinking that I need to revamp the description because it's kind of dull. Part of me was thinking, Oh, just tell them what it's about, you only have to sell people on the first book anyway. Which is really a dumb approach, right? There's aliens and cussing and aliens trying to understand cussing and a spaceship crash and excitement! I should at least try to make it sound entertaining.

We'll see when I get around to that--the houseguest is here, so the next couple of weeks are going to be busy-busy.

App makers, Tin Pan Alley, and indie writers

This article in the Wall Street Journal draws a lot of parallels between today's app makers and the Tin Pan Alley musicians--there's a big market and barriers to entry are low. The problem is getting people to notice you. (Hey, notice any parallels between those two businesses and a certain third?)

Marketing and selling the app remains a crude undertaking. It's still difficult for users to discover new apps much beyond Apple's "Top 10" lists. As in Tin Pan Alley, a mercenary world of gimmickry and "hit-making" middlemen promise to push an app onto these charts. Song-plugging has even returned. Today it's called "pay per install"—in which app developers pay anywhere from a quarter to a few dollars for each app download....

Typical costs now run roughly $1.50 to $1.80 per installation, a stiff sum for a free or 99-cent app. Games companies are now spending 60% to 70% of their gross income on this marketing, he says.

It's both interesting and a kind of cautionary tale: There's pressure to lower prices in the face of all the other products (a pressure that I think is more intense because people are cranking out "me-too" apps by the dozen, and the only way for those to stand out is by being cheap), but if you lower your prices too much, any money spent marketing will necessarily be a complete loss.

Collectives, cooperatives, and groups

I've been pondering writing collectives/co-ops/groups for a while now--not critique groups, but organizations of writers who work together to promote their work.

I'm interested because I've seen how effective group promotions can be. Offering a Smashwords coupon by myself isn't nearly as effective as taking part in their annual e-book sale. That seems to be a major draw for something like the Indie Book Collective--I think that when I put Trang into KDP Select I will also look into taking part in something like that.

The other thing is that groups can do certain things that individuals aren't really allowed to do. For example, I took part in a Meetup group focused on e-book production and promotion. One of the people there went to a sci-fi con, hoping to pass out promotional material for her books, and felt very overwhelmed. Well, back in my Browncoat days, we'd get tables at sci-fi cons to spread the word about Serenity--if your organization isn't selling anything and you put in your request early enough, you can usually get the table for free. Hanging out at a table full of promotional material is presumably less intimidating for the writers, while said table full o' goodies is presumably more interesting to the readers.

So, using the Meetup group's name, I put in a request for a table at Foolscap, and they gave it to us. Immediately, the group stopped meeting (oops), but I'm hoping that people with books out are still interested in doing it. (In fact, if you write speculative fiction, live in the Puget Sound area, and want to participate, fill out that "Contact Me" form over to the left there. I'm encouraging people to do actual promotions--coupons, links to free fiction, whatevs--rather than just boring ads that say, "Read Me! I'm Awesome!")

We'll see how it goes, but you know, if doing a table works for the readers and works for the writers, it seems silly to not do it. There needs to be an organization, though--the cons would be a lot less willing to offer a free table to an individual writer.

Another thing that might be easier for a group to do is to sell to independent bookstores. Obviously this would not be easy, just easier--you'd have to do the Web site and flyers (which would be an up-front cost). But if it's a question of getting enough paper titles together to have a catalog, that's going to be a lot easier for a group of writers to do than an individual.

People talk about this sort of thing here--it does sound like a lot of these groups are very author-centric, with people just Tweeting about how awesome other group members are, which I don't think would be helpful. (And some of it is really just regular writing-buddy type stuff.)

In some cases they pitch in to buy ads together, which could be helpful. I suppose you and a writing pal in the same genre could decide to split the cost of an ad in Romantic Times or Locus or whatever. On the other hand, if it were an on-line ad, where would the link take you? There would need to be a Web site with links to both writers' e-books--so you're back to an organization....

Writing & depression

Anne R. Allen has a though-provoking post on writing and depression. I always question the notion that writing causes depression--I think a lot of people who go through hard times write as a coping mechanism, so they can be correlated without the former causing the latter. Also writing requires solitude, and a lack of social connections is correlated with depression, and then if you throw in how impossible it's become to succeed in traditional publishing.... But I will admit that I probably do my best world building when I'm a little bored, somewhat isolated, and not terribly happy.

It doesn't mean much now...

OK, I am doing the truly mindless task of re-addressing the links in old blog posts. I got all the ones that point to the old LiveJournal blog out, which was a real pain because I had to look those posts up to get the address. Now it's just yanking the Web host's name out of the addresses, which goes much faster (although I am beginning to wish that I was both a less-prolific blogger and less industrious about linking to every last old post).

Like a lot of things--like getting the book into less-populated categories, or doing a large-print edition, or even doing social media--there's no immediate reason for me to be doing this. I'm happy with my Web host; I haven't had any problems with it.

But is that always going to be true? I was happy with LiveJournal, until I wasn't. I think it's important to position yourself so that you won't be locked into a situation in the future that you might not like. It's kind of an omnivorous approach to publishing--try different things, because you don't know what might pay off, and you don't want to become so narrowly focused on one approach that you can't adjust to change.

Progress report

Done! DONE! DOOOOOONNNNNNE!!!

I'm very happy about this.

Being thrifty with covers

In a comment to my last post, Jim Self noted that it's worth it to invest in covers--be it time or money.

I agree wholeheartedly, and I would throw in another thing you really should invest: Thought.

Thought was something I decidedly failed to invest when I released Trang. I released it with no cover at all, because I knew something deep down in my bones: A cover artist was going to take care of all that.

Didn't work out that way, did it?

The thing is, I'm actually happy I didn't pay someone to do the cover initially. Why? Because my concept was all wrong.

Here's that hideous cover I drew myself. (Warning: I cannot draw. At all. I have a seven-year-old niece who draws a THOUSAND times better than I do.)

If I had paid someone a lot of money for a well-drawn, far-prettier version of this cover, it would not have helped. Even with the horrible drawing, the cover was quite effective in communicating the idea that Trang is wacky adventure sci-fi, which it is not. Of course that upset readers who wanted that kind of book. If I had spent a lot of money, that would not have improved the fundamental problem in communication--indeed, it might have attracted many more people who were never going to like this kind of book.

Plus, if I had spent a lot of money on a beautiful version of the cover, I might not have scrapped that cover concept quite so quickly (loss aversion!). Not only did I save money, but I made it easier to test cover ideas and discard those that do not work. (Not that I realized it at the time.)

And as Lindsay Buroker discovered, you can have a professional cover that is technically excellent but that just does not get the job done--simpler is in many ways better.

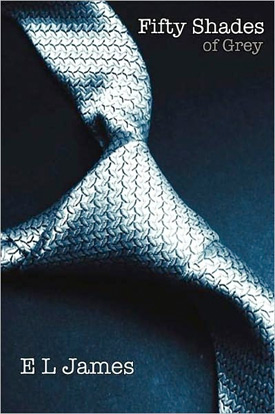

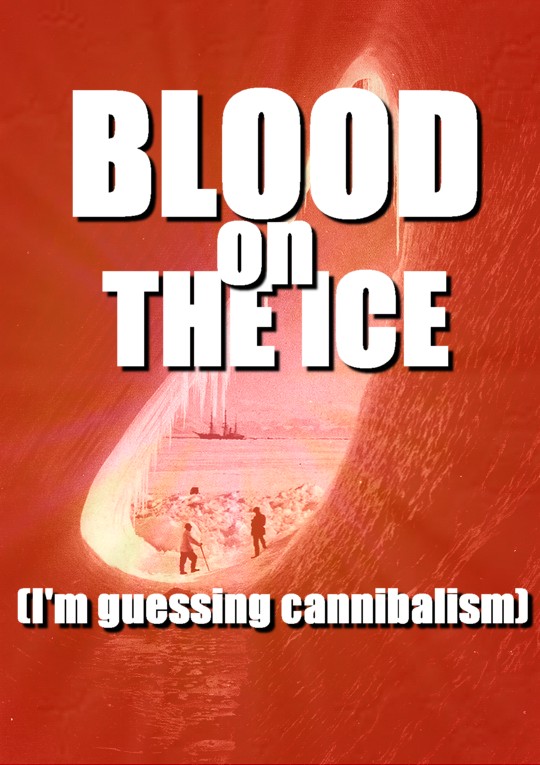

Witness:

That's the power of good design right there--it's a very simple image and (I believe) a standard font, but the result is both eye-catching and suggestive of the book's content.

But what can you do if you aren't the least bit artistic?

Well, for starters I would question the idea that you aren't the least bit artistic. You have opinions, right? You can say "ugly!" and "pretty!" Certain things, you notice.

Take advantage of that fact. Notice what you notice.

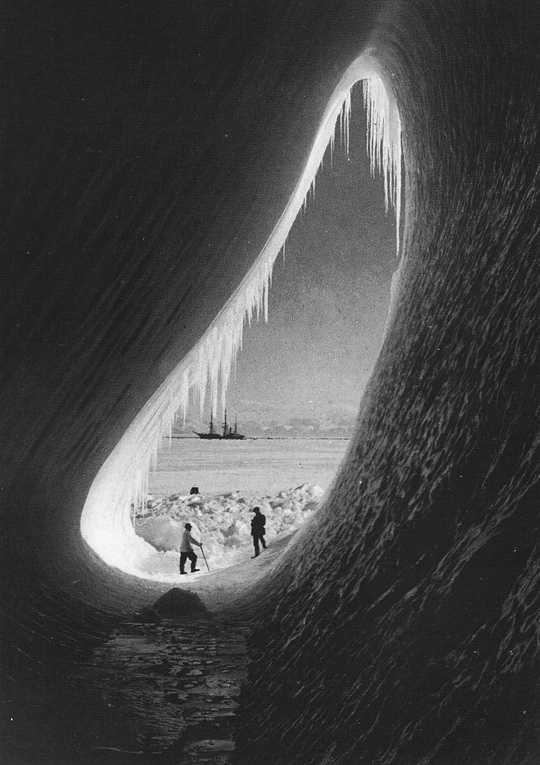

For example, Passive Guy recently linked to The Public Domain Review, which is seriously awesome. (Yeah, if you can't do anything when there's stuff like this and this and this and this out there, I can't help you.) He posted this picture:

My first thought was, "That's eye-catching! That would make a great book cover"

Noodle with it a bit more, and it's a science-fiction cover!

Really, the possibilities are endless....

And this is just me screwing around for a little bit because I don't feel like tackling that layout. (I would noodle with the lettering to improve visibility if this was something that actually mattered.)

I'm not artistic. I don't even have real photo-editing software--just a freebie program that came with the computer I had before I got this one. Imagine what I could do if I had real software and actual talent, like Passive Guy and Barbara Morgenroth.

Both of them are also good photographers--I'm not, but I know a few good hobbyists, so I could crib off them. And basically, whenever anything catches my eye, I try to make note of what works, and if possible, how it works. (This is sometimes kind of a problem, because most visual artists aren't that good with words, so they often literally can't tell you what their process is.)

For example, if I was trying to put together a cover for a thriller, I would be cribbing big time from Carl Graves, Joe Konrath's cover artist. If you look at the way his lettering is positioned, he tends to guide the eye to the middle third of the book, and he'll even throw in some rays to pull it in. (Oh, and what's that I see on the photos? iStockphoto lettermarks!)

The small business perspective: Starting up!

I'm certainly not the first person to note that when you start to self publish, you're starting a small business. Which, like I said, is nice, because you don't have to reinvent the wheel.

You do, however, have to recognize that your small business is not really like the average small business.

Compare writing a book to, say, opening a small retail operation. The good news: Your start-up costs are laughably tiny compared to having to rent or lease a retail space.

The bad news: Well, if you're buying scarves for $20 and selling them for $30, and you know how much foot traffic a place gets, you can make a fairly decent estimate of how many scarves you can sell. You can talk to other scarf-sellers in similar locations; you can spy on the guy who, say, sells sunglasses in the shop next to the place you want and see how much he sells.

In other words, you can plan. In fact, writing a business plan is one of the basics of starting a new business.

If you write a book, you have no idea how much you'll sell!

Am I exaggerating? No. Look at Kristine Katherine Rusch's latest post (which is a really good one, by the way). She notes, "I have books that sell really well and books I can’t give away." Most writers say the same--some of their titles do great, some don't sell well at all.

The problem is that with your first book, you don't know where you're going to wind up on that continuum. Hence the advice to Keep Writing, even if your book doesn't do well, because the next one may do better.

Rusch's husband, Dean Wesley Smith, says to think like a publisher and to project your likely income from your books. He hedges this around with lots and lots of caveats, but honestly, I don't even think that's worth doing if you don't have a track record.

When Smith cranks out his gazillionth Poker Boy story, he's got a rough--and more important, a realistic--idea of how it's going to sell. There are X many Poker Boy fans out there, and that can help Smith decide whether it's worth it to spend time on a Poker Boy project rather than another one.

If you've never produced a book before, you can't do that. I think the temptation is to build castles in the sky and say, Oh, I'm sure to sell a bunch here and I'll sell a bunch there and I'll sell a bunch there, too! But you don't know that you'll sell a single copy.

Which is why I'm a fan of starting small--and I don't just mean by starting with an e-book. Some of the advice I've seen for new writers about handling the business side of things is just insane. I was a full-time freelancer for many years and I never:

1. Incorporated (my father was in business for 40 years and he never incorporated--he never thought it made financial sense)

2. Had dedicated bank accounts for my business

3. Bought fancy equipment for my business

4. Rented space for my business

5. Registered a business name

Why not? I didn't need to, and I would look long and hard about your "need" to, say, shell out for an office or cough up hundreds or even thousands of dollars in accountant fees because you think that means you're serious.

You're serious if you write. Everything else is just froufrou.

But I'm supposed to aim high! you cry. Again, it is very easy to confuse the trappings of success with the strategies that allow you to be successful. The trappings of success are what's so expensive.

One thing you'll get told (over and over again, by people who have not the slightest idea what they are talking about) is that, hey, you should spend lots of money on your business because you get a really nice tax break!!!

Not really. Money you "write off" when you spend on your business comes out of your taxable income. So, let's take two people, who both make $40,000 on their business.

Person A spends $1,000 on business stuff, leaving them with $39,000 in taxable income.

Person B spends $10,000 on business stuff, leaving them with $30,000 in taxable income.

Person A pays $5,881 in taxes (I'm using the 2011 tax tables and assuming they are single)

Person B pays $4,079 in taxes

Person A is left with $33,119

Person B is left with $25,921

Person B spent $10,000 to save $2,000. That is not good.

Don't let people talk you into to spending like a drunk sailor on shore leave. Spend money after you get it, not before (Smith and I are 100% in agreement on that one). The after-not-before approach means that you won't set yourself up so that if you don't make a certain amount of money by a certain date, you face catastrophe. Remember--you have no idea if you'll sell even a single copy. No idea. Don't put a deadline on your finances; save them for your writing.

Obviously if you have the means (or score big on Kickstarter), you can do what you want, but if you don't, make your book earn its keep. After-not-before means that you pay to have a paper book made after you sell enough e-books to pay for it. After-not-before means that you buy expensive custom cover art after you sell enough books with stock-photo covers to pay for it.

Does this require patience? Yes. Does it require discipline. Yes. Does it mean you'll have to ignore the people telling you that you're sabotaging your own work? Yes. If anyone gives you a hard time about you not being ambitious enough, sweetly ask them if they plan to pay for whatever it is they're insisting you do.

But don't borrow money from them.

Of course businesses borrow money all the time, but again, given the low overhead for a self-published author, there's no need to. And it tends to stress the finances.

I've likened a traditional publishing contract to a really bad loan. But thinking about it, I think a traditional publishing contract is actually a lot more like venture capital financing.

Now, if you don't know much about venture capital, and if you lived through the late 1990s, you probably think of venture capital the same way most people think about traditional publishing--it's Santa Claus coming to your door with a big bag of money.

That's what I thought when I first became a business reporter. Imagine my surprise when I'd ask a local tech startup, "Are you looking to get VC funding?" and the owners would look at me like I'd just asked them if they were planning to raise funds by selling their own children to pedophiles.

It turns out that venture-capital funding operates with a lot of the same limitations as traditional publishing. To wit:

1. You lose control of your business. Bye-bye, you.

2. They operate on a limited time frame. In that era, the typical VC fund wanted to be able to take the company public (which means making it big and of interest to a wide swath of investors) within 3-5 years. If the company grew more slowly than that, it was trashed.

3. It is a volume game for them. Most companies couldn't possibly grow that big that fast, so the VC funds scrapped them--shut them down and sold off the parts. They made their money on the few companies that could indeed grow that fast. So it wasn't about nuturing companies, or having really good management: The expectation was that the majority of companies would be destroyed by this process.

Of course, if you sold out to a venture capital fund, you made some money--just like if you get a traditional publishing contract, you'll make some money. But it was truly selling out--if you cared or wanted what was best for your company or simply wanted the most money, you didn't do it.

Progress report

That shrieking noise you heard was me realizing that I started Chapter 27 on the wrong page. It's OK. That meant two chapters to layout AGAIN, but 1. it was just two chapters, 2. one of them was the short epilogue, and 3. neither took very long. I also fixed that chapter (the infamous Chapter 13, of course) that needed to be expanded by a page. And I realized that I had italicized the page numbers on one side of the spread but not the other; they are now roman on both sides for improved readability.

I input the text fixes into the e-books and uploaded them. I also input them into the regular paper version--in some cases I decided that single paragraphs would read better if broke them into two, which affected that layout. So now I've printed out all the chapters that had significant alterations, and tomorrow I will read over them, make any corrections, then compile the chapters into books again and upload them onto CreateSpace.

AND THEN I WILL BE DONE! DOOOOONNNNNE!!!!

I am once again famous for cussing....

Stephen Merlino, who beta'd Trust and who is an excellent writer, put some excerpts from it up on his blog. They are from a scene told from the point of view of an alien who is using a translation device that, in Steve's words, "struggles to decode the expletives of the human space marines assigned to protect Trang." Now he's curious to know if other cultures are as fond of scatological and sex-based swears as English-speakers are, so if you know about that, go on over there and tell him!

And if you've read Trust and are going, Wait, the Giant Mankiller doesn't look like a T-Rex! know that Steve read an earlier version in which the Giant Mankiller wasn't described at all--he told me to fix that, so I did.

Progress report

I blew off yesterday, but today I read up to chapter 25. I caught something that is going to make a chapter one page longer, but I think I can make it two pages longer and therefore not screw up the layout from that point forward. Because I am really, really ready to be done with this layout!

You're running a small business--and that's a good thing!

I first became a full-time freelancer by accident. I was working in the encyclopedia industry and (you know where this is going) I got laid off. They then offered to rehire me as a freelancer.

Sounds like I was getting screwed, right? The thing is, I was horribly bored editing, but I was too risk-adverse to move on to something else. The layoff was the kick in the pants that I needed: I decided to go to journalism school. But of course I needed to earn a living in the meantime, so I jumped at the offer.

The pay was good, there was a ton of work to do, I already knew the job, and I could do it from home. Excellent!

Except that this was the place where the people who needed freelance work done were in NYC, and the people who paid the freelancers were in Ohio. The Ohio crew didn't care whether or not the work actually got done (in fact, that project got trashed after it was finished instead of going to the printer). Sure enough, the checks started coming later and later and later....

What with the layoff and all, I had a pretty good idea that this company was going down, so I had already started freelancing for other people (or freelancing more--everybody moonlights in publishing). I caught some flak for this from the poor encyclopedia editor, who wanted me to work on his project all the time. But I was like, I have to pay the rent at the first of every month no matter what those jokers in Ohio do. Sorry, but...

I must have many clients.

I didn't realize it at the time, but I was being quite astute. Years later I was reading through a business magazine, and they had an article on how to run a successful small business, and one of the major pointers was:

You must have many clients.

Why? Because that way if one client screws you, you don't go down in flames.

The temptation is not to diversify--it takes work, and people are lazy. And if GinormoMegaCorp offers you a huge, extremely lucrative contract to work with them, you of course will get all excited and wriggly like a puppy and you will drop all your other clients and you will run right over to latch yourself onto the GinormoMegaCorp teat. And you will forget that she's actually just a big old bitch who will snap at you and take off whenever the mood strikes her.

All small business people struggle with this. All of them.

All of them struggle with the fact that you never have start-up capital when you're actually starting up. All of them struggle with the fact that you don't know when--or if!--you'll start making money with your business. All of them have to remind themselves to Keep costs low when there are so many enticing ways to spend money. (Spending that will help the business "in the long run"--you know, like after you file for bankruptcy and a creditor swoops in and takes over your brand and profits off all that start-up spending. Happens all the time.)

The nice thing is, they talk about it. You are not alone! There's a whole section on the U.S. Small Business Association's Web site about funding your business! There are countless articles and Web sites about running a small business! (There are also countless people who want to take your money, but ignore them.)

You don't have to reinvent the wheel. Yes, contemporary self-publishing is a new business, but it's still a business. You can learn from other business people.

Let's take You must have many clients as an example. This is why I get nervous when people act like they should retail and market only through Amazon. Of course I don't ignore Amazon--Amazon is important. But the minute you start acting like Amazon is your only client, you are setting yourself up to have the rug pulled out from under you.

Plus, you're losing sight of the fact that Amazon is not actually a client--your clients are your readers, and Amazon is just one way to reach one group of clients. Likewise traditional publishers are not clients, they are just one way to reach another group of clients.

There are so many other examples of small business advice that applies to self-publishing:

Your competition is not your enemy, or even really your competition. Works if your products aren't interchangeable, which books are not. Crate & Barrel and The Container Store boost sales by operating side-by-side. Think of the Chinese food district. Can you do something like that with your books and books by other authors?

Get diverse perspectives. Writers tend to talk to other writers--that's our "affinity group." Most readers are not writers: They don't haunt bookstores and worry about the future of editing; instead, they go to feed stores and hang out in gun forums.

Existing clients are your best clients... They're cheaper to reach and easier to sell to. This is why writing lots of books works so well: You've got a base already. It's also why I think it's worth it (if you can afford it--see Keep costs low above) to have multiple formats available: People will indeed buy the same book twice if they want to give it as a gift or listen to it while they exercise.

...but they must be reminded that you exist. The seasonal businesses in that article have to remind people they exist each year--much like writers have to each time they come out with a new book.

Track promotions. That seasonal business article actually has some good advice on that one--the more you do, the less money you will waste. Derek Canyon shows you how to track returns on advertising expenditures, and Lindsay Buroker outlines the revenue-per-customer limitation--if you're paying a dollar in marketing for every client acquired, those clients need to be giving you more than 35 cents.

More generally: Realize that there's a community and knowledge bank out there. What you're doing isn't easy, but many, many people have faced similar challenges. They may wear suits and be Rotarians and refuse to read fiction, but they are your people. You can learn from them.

Why I want a Mac

Look at that! Look at those ornaments!

Oh, yes, I know, they have Scrivener for Windows nowadays, but you know it only works about 90% as well, and that final 10% is what allowed that to happen. And my computer couldn't run it anyway because Adobe Acrobat is taxing its CPU to the nth degree already....

I am terribly jealous, if you hadn't figured that out yet.

Space...opera?

Today I was watching my niece, but I took advantage to her tragic addiction to Wild Kratts to do some noodling with Amazon categories. Having realized the hard way that the Trang series is not, in fact, adventure sci-fi, I've been classifying it as general sci-fi. But now that I actually have two books out and it is actually a series, I e-mailed Amazon asking that it be placed as well into the Kindle category "Science Fiction: Series," which still has less than 200 books.

Oddly enough, there is no "Science Fiction: Series" category for paper books. (Why not, I do not know.) That was kind of a bummer because there are freaking 86,419 paper books classified as general science fiction. But in the paper books categories there is a subcategory "Science Fiction: Space Opera," which has over 5,000 books--still a lot, but better than 86K, am I right? (No? That's still too many books for it to matter? Have you tried shutting up?)

And I was like, "Space opera? Didn't some of the people who reviewed Trang call it a space opera?"

The thing is (and according to Wikipedia, this dates me) I never considered calling something a space opera any kind of compliment. Space opera = soap opera in space = histrionics and bad dialogue.

But apparently kids these days (like Brian Aldiss, who should get off my lawn) use space opera to mean "the good old stuff." (Hey, aren't I marketing these books as 1960s retro sci-fi? I believe I am!) And if you're going to define it as "colorful, dramatic, large-scale science fiction adventure, competently and sometimes beautifully written, usually focused on a sympathetic, heroic central character and plot action, and usually set . . . in space or on other worlds, characteristically optimistic in tone" I'll definitely take it!

("Military space opera," though...hm. One of my beta readers thought Trust would appeal to military readers, but my concern is that most of the problems in the series are solved via diplomacy--i.e. talking, not shooting--which is likely to annoy most fans of military SF.)

Most important, if you look again at first page or two of the books categorized as space opera on Amazon: Ender's Game, The Hitchhiker's Guide, The Martian Chronicles, Hyperion, a Vorkosigan saga book--need I mention that these are all books I love?

OK. It's on the to-do list--when I input the latest corrections, I shall re-classify both Trang and Trust as...space opera! I fully expect Opera Man to swoosh through wearing deely boppers when I do.

Progress report

I read through up to chapter 11--very few art errors are left, I'm happy to say. I haven't quite reached the point where I'd rather put my own eyes out with my trusty red pen than read Trust again, but it's safe to say that I'm getting there.

The power of a book in hand

I linked to this in my previous post, but it's a Wall Street Journal article, which means it probably won't be available to read for long. So I wanted to go into a little more detail on it.

Here's the gist:

Author Michael Ennis submitted a draft of his novel, "The Malice of Fortune," to New York publishing houses but was rejected. He revised, edited and submitted once more but was rejected again.

Then he got a tip from his agent: Try booksellers first.

Mr. Ennis and agent Daniel Lazar of Writers House self-published bound galleys of the novel using Lulu.com and a local print shop, and sent 48 copies to influential booksellers such as Mitchell Kaplan of Books & Books in Miami and Sarah Harvey of Tattered Cover in Denver.

Out of those, 23 booksellers responded enthusiastically, writing strong praise for the book. Using such quotes, Messrs. Ennis and Lazar submitted the manuscript a third time to publishers. Within days, Knopf Doubleday snapped up U.S. rights to the book for a six-figure sum. Doubleday, an imprint of Bertelsmann AG's Random House unit, will release "The Malice of Fortune" on Sept. 11, with a first-print run of 75,000 copies.

This might at first seem different from someone self-publishing, building a up a sales record, and then getting a contract, but really it's not. It's someone using their self-published book to indicate to publishers that it does indeed appeal to a particular audience: Bookstore owners. Doubleday is willing to gamble that a book that appeals to that niche will have big sales.

Once again, actually having a book available is key. There's value in that.